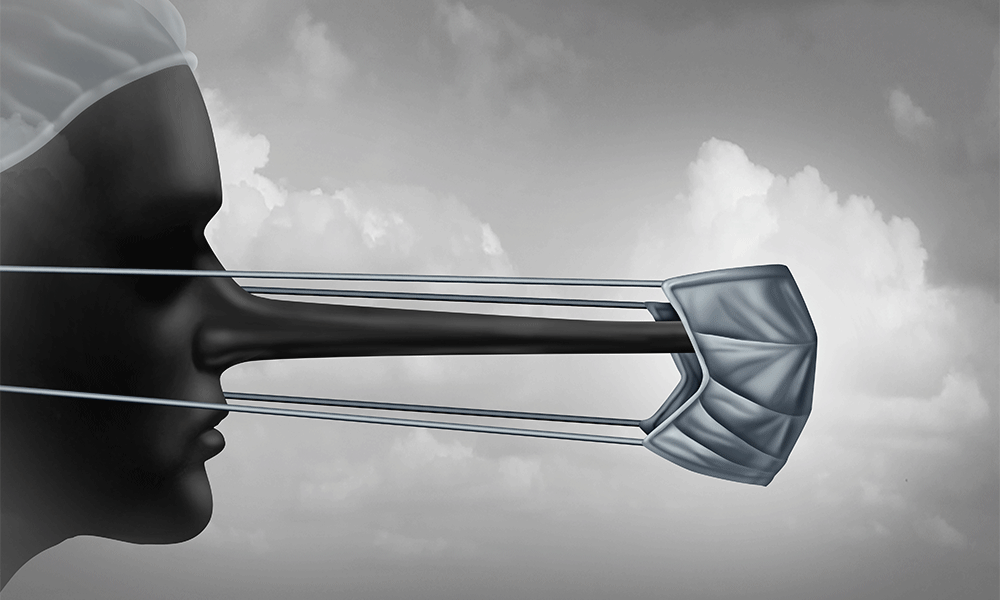

Is It Ever OK to Lie to Patients?

Honesty may be the best policy. But is complete truthfulness the compassionate course in every case? Here's what you need to know about the legal, ethical, and professional issues around withholding information from patients.

If there's one thing sacred in the doctor-patient relationship, it's trust. Open and honest dialogue on both sides of the exam table is by all accounts critical to effective care. Patients have to be truthful to ensure diagnostic accuracy and an appropriate treatment plan, while doctors need to provide full disclosure about their patient's health - the good and the bad- to help patients make informed decisions. Indeed, patient autonomy is the cornerstone of modern medicine and patient-centered care.

That patients are entitled to the truth, then, is a given, but just how much doctors are obligated to reveal is in fact a matter of much debate - particularly as it relates to the sick and dying. Physicians are often forced to balance compassion with the patient's right to know. There are patients, for example, who are too emotionally frail to be told about the progressive symptoms of their disease. There are accident victims who are alert enough to learn of a loved one's death - but whose relatives ask that the news be delivered later by a family member. There are elderly patients with dementia who would be mercilessly forced to relive the loss of a spouse on a daily basis. There are adult children who demand that you spare their elderly parent from a grim diagnosis. And there are patients whose cultural beliefs differ greatly on the topic of medical disclosure. Such scenarios beg the question: Is it ever appropriate to spin the truth or withhold information from a patient? Is it ever OK to lie?

"There are rarely cut and dry ethical issues because you've got competing interests," says Nancy Berlinger, a research scholar who specializes in end-of-life healthcare ethics at The Hastings Center, an independent bioethics research institute in Garrison, N.Y. "It's very complex. No one in medicine gets up in the morning and says, 'I'm going to lie to people today.' It's more about saying, 'How do I balance my obligation to be truthful with my desire to be compassionate and how does that work, really, in practice?'"

The law

Informed consent wasn't always the mantra. Thirty years ago, cancer patients in the United States were frequently misled about the extent of their illness. "I remember being in medical school years ago and being distinctly told that when a person has lung cancer, never tell them they have lung cancer," says Peter Dixon, a former oncologist and current primary-care doctor with a geriatric group in Essex, Conn. "We were told to give them a dose of morphine and wash our hands of it. Things have certainly changed." Today, doctors are expected to treat patients as partners, delivering a complete picture of their prognosis and treatment options so patients can take an active role in their own healthcare.

Aside from the ethical mandate of truth telling in the modern age of medicine, physicians in most states are also legally obligated to disclose all relevant health information to patients. At least one exception, however, exists. Earlier this year, the Oklahoma legislature passed a law that prevents women who give birth to a disabled child from suing a doctor who misled them or outright lied about the health of their baby while they were pregnant - including cases where the fetus had a fatal anomaly that would not allow it to live outside the womb. Bill sponsors say the law is designed to prevent lawsuits by women who wish, later on, that their doctor had counseled them to abort. But opponents say it protects physicians who mislead pregnant women on purpose, to prevent them from having an abortion.

Sean F. X. Dugan, a medical malpractice defense trial lawyer and senior partner with Martin Clearwater & Bell LLP in New York, says he's also starting to see some "cracks in the citadel" over which parties physicians are obligated to be truthful to. "The law clearly indicates that the physician's fiduciary obligation runs to her patient - period," says Dugan, "But over my 30 years in practice, I've seen that iron-bound rule start to crack." In recent years, he notes, several lawsuits have been passed up through the courts in which a physician informed the spouse of a patient who was diagnosed with a life-threatening sexually transmitted disease. "Once, that would have been summarily dismissed, but now we as a society are beginning to dip our toe in the water," says Dugan. "Some courts are now beginning to say that maybe, under those circumstances, the doctor should go beyond the physician-patient relationship, and that they have a duty to disclose information to another party if they know someone is in danger." Where to draw that line is the trick. Consider patients with a contagious and deadly disease who live with someone they are not married to, or with young kids.

A case for compassion?

While outright lying to patients is rare, many physicians (particularly oncologists) say that at some point in their career they have failed to answer questions directly, given incomplete information about the burden or benefit of treatment, and otherwise avoided "imminent death" discussions with patients suffering from an advanced disease, says Thomas J. Smith, professor of internal medicine, hematology/oncology at Virginia Commonwealth University and cofounder of the Thomas Palliative Care Unit at VCU Massey Cancer Center in Richmond, Va. Just 37 percent of terminally ill patients, he notes, have explicit conversations with their doctor about the fact that they are going to die from their disease.

The most common argument against obligatory truth telling is the impact it may have on a patient's physical or emotional state. Healthcare providers in other parts of the world, like central Asia and the former Soviet Union, still censor information from cancer patients on the grounds that it causes depression and an earlier death. "None of that is true," says Smith, whose study earlier this year found that giving honest information to patients with terminal cancer did not rob them of hope. "Most patients, certainly in the Western world, want to know what they have, what their options are, and what's going to happen to them."

Above all else, Smith notes, patients want assurances that their doctors and nurses won't abandon them when their treatment options run dry. "When there's nothing left to be done to make the cancer go away, there are still lots of things to be done to help that person adapt to their new reality and maximize the time they have left," he says, noting the benefits of knowing the gravity of their condition far outweigh sparing patients from any anxiety. Disclosure enables patients to plan - to create a will and living will, make their wishes known to family members, pass along what they've learned to loved ones, name a durable power of medical attorney, decide where they want to spend the rest of their life, and make spiritual and family member amends. "You get the chance to do what some people call a life review," says Smith.

Indeed, most studies over the last decade found that patients who were told candidly they are going to die lived just as long, had better medical care, spent less time in the hospital, and had fewer "bad deaths" - those whose lives ended in the ICU, ER, or with CPR - than those who were not. A 2008 study of 332 terminally ill patients and their caregivers by researchers at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute also found that patients who had end-of-life discussions were not more depressed, worried, or sad than those who did not. Instead they were far more likely to accept their illness and preferred comfort care over aggressive life-extending therapies, which often create upsetting side effects and hamper communication with loved ones. Interestingly, these results of full disclosure also had a "cascading effect" on the patients' loved one's ability to cope with their loss. Individuals whose loved ones died in an ICU were more likely to develop a major depressive disorder than those whose loved ones did not receive such intensive care.

What's your motive?

Another reason doctors give for creating a less painful truth is that a full discussion takes too much time, the same reason doctors cite for their reluctance to initiate DNR discussions, says Smith. "It does take more time to say, 'Let's talk about your illness and how you're coping with it,' than it does to say, 'Well, the next chemo we're going to try is XYZ,' because if you start talking about the fact that that treatment has a marginal if any benefit and that person is going to die sooner rather than later it takes a lot longer," he says. "A good doctor will sit and listen to the answers and that takes time."

And then, of course, there's the simple fact that it's tough. "The real reason doctors avoid having these discussions is that it's just really hard to look another person in the eye and tell them that there's nothing more that can be done to make them live longer or give them a miraculous chance of a cure," says Smith. "Anyone who says, 'Oh, that's just part of your job,' probably hasn't done it very much."

It's all in the delivery

Dixon says an important part of delivering difficult truths to your patients is learning how to read your patients' personalities. While all are entitled to the truth about their condition, some are satisfied with a broad picture of their illness and the options available. Some need a greater degree of detail and others need it all in small doses. Patients facing death also differ significantly in the type of medical care they wish to pursue. Some, particularly younger patients, will seek more aggressive treatment options, while others (primarily the elderly) just want your support with as little medical intervention as possible. "If you sense that you're going too fast, or that it seems too scary, you can say, 'Look, sometimes we talk awfully fast. Do you want to stop here and come back next week and talk more about this? We don't need to do it all right away.'"

Remember, too, that honesty and an emphasis on the positive are not mutually exclusive. "You need to focus on what's important about their condition, but there is an art to presenting things to people in different ways," says Dixon. "You can give bad news but put a positive spin on it. When patients come to me with a spot on their liver from an X-ray, their primary-care doctor has already told them they have cancer. When they see me, I can say, well, 98 percent of your liver looks great."

When faced with family members who wish to shield their aging parents or grandparents from a poor prognosis, Dixon says he simply levels with them. "I don't think that's fair to the person who is sick," he says. "I express my opinion, that I'm not comfortable with hiding things. You don't have to go into explicit detail [about their fragile state] and you can be more general, but I tell them to put themselves in the patient's shoes and think about what they would want."

Though doctors in private practice rarely encounter such scenarios, physicians who work in a hospital setting may also be asked by the friends or family of an accident victim to delay information about another passenger's death until a parent can break the news. In those cases, says Berlinger, it's a judgment call. "It would have to be clear how long we're talking about - an hour or four days, because if it was several days that might be tantamount to deception," she says, noting this is a case where a hospital ethics consult can assist. "It's about the information, but it's also about providing support to a person who is getting bad news. It's a very stressful situation and they need to feel continuity of care - that someone, like a nurse, their doctor, a chaplain, or a family member, is sticking with them and attending to their emotional needs."

Whatever your motivation for being less than truthful with patients, Berlinger says, there is really never good cause to keep patients in the dark. "If a doctor is considering withholding information, the first thing they have to ask themselves is why would I do this - given my obligation to disclose information to my patients and their right to information about their own health?" she says.

For most patients, full disclosure about their condition takes fear off the table. "One of the problems is that physicians don't level with people and discuss openly what happens next and what to expect - what you're going to feel like," says Dixon. "When people are prepared they're not afraid anymore."

In Summary

Treating patients is a complex business. Sometimes you have to have tough conversations with patients about their diagnoses. Is it ever appropriate to spin the truth or withhold information from a patient? Consider the following:

• In most states physicians are legally obligated to disclose all relevant health information to patients.

• Is it more compassionate to patients to withhold upsetting details about life-threatening diseases or to give them the comfort of knowing the truth and making their own decisions about the end of their lives?

• Physicians should examine their motive for withholding information: Is it compassion, fear of the time it takes to have more involved discussions, avoidance because it's hard to deliver such news, or something else?

Shelly K. Schwartz, a freelance writer in Maplewood, N.J., has covered personal finance, technology, and healthcare for more than 12 years. Her work has appeared on CNNMoney.com, Bankrate.com, and in Healthy Family magazine. She can be reached via editor@physicianspractice.com.

This article originally appeared in the November 2010 issue of Physicians Practice.

Newsletter

Optimize your practice with the Physicians Practice newsletter, offering management pearls, leadership tips, and business strategies tailored for practice administrators and physicians of any specialty.